How Matt LaFleur Could Change How the Packers Use Their Running Backs

It’s hard to draw a lot of firm conclusions about how Matt LaFleur could change the Packers offense. We know things are going to be different, but seven months before anything resembling actual football will be played, any analysis will be largely conjecture.

However, conjecture isn’t always inaccurate. On a recent episode of Blue 58, we discussed LaFleur’s use of tight ends in the Tennessee Titans offense. As a brief summary, LaFleur used tight ends very frequently in Tennessee, deploying them far more often than the Packers and using them in vastly different ways.

I thought it was fair to draw some conclusions about how the Packers could use their tight ends based on LaFleur’s Tennessee tendencies for a couple reasons. First, LaFleur still used tight ends regularly despite losing Delanie Walker, his best tight end, early in the season.

Second, LaFleur’s tight end use shows us something important: he uses tight ends differently than both Kyle Shanahan and Sean McVay. LaFleur is closely linked philosophically to both Shanahan and McVay but uses multiple tight end sets more frequently, small but significant proof that he has a firm offensive mindset of his own. This seems like strong evidence that LaFleur will continue to use tight ends regularly and in great numbers in Green Bay.

All this to say that it’s okay to project a little bit. And continuing that projection, it seems likely that LaFleur is going to do some very interesting things with the Packers’ running backs in the passing game.

LaFleur’s offenses throw the ball to running backs

Throughout his career, the offenses in which Matt LaFleur has been involved have done a great job of getting the ball to running backs.

Dating to his first NFL job in 2009, LaFleur’s teams have thrown the ball to running backs far more frequently than the Packers. Not counting his one season with Notre Dame, the top receiving back on LaFleur’s teams have averaged 47.8 catches per season for more than 400 yards.

In that same stretch, the Packers’ leading receiving back has averaged just 32.8 catches per season for less than 270 yards.

Some of this has to do with personnel, to be sure, and LaFleur was only in a play calling capacity for one of the seasons on the chart below. But he was significantly involved in the offense in each of these seasons, and I believe this shows LaFleur has deep schematic roots when it comes to getting the ball to running backs.

Here’s how the stats break down on a year-by-year basis:

Why getting backs involved in the passing game is good

There are three straightforward reasons why getting the ball to running backs is good for the Packers.

Improved versatility

First, it will immediately make the Packers’ offense more versatile and harder to defend. This is a simple math question. Too often, the Packers have allowed opposing defenses to get away with guarding only four players. If the defense can all but ignore the running back in a passing play, it frees up another defender to make life difficult for the various receivers and tight ends on the field. If the running back is at least a nominal threat, it will make life that much easier for the rest of the potential pass catchers on the field.

Better options for Rodgers

Second, involving running backs in the passing game most substantively could encourage Aaron Rodgers to utilize them more. Rodgers’ reluctance to check down to backs was well documented in 2018, but a significant part of that reluctance was justified because of how the backs were being used. Mike McCarthy rarely used his running backs as anything more than a dump-off option. There was very little sophistication in the routes Packers backs ran under the previous coaching regime. If LaFleur can give Rodgers better options via better routes for running backs, Rodgers could be more willing to look their way.

Less wear and tear on Aaron Jones

Finally, throwing the ball to running backs more frequently could save some wear and tear on Aaron Jones. A slightly built back, injuries have ended Jones’ first two seasons with the Packers. There’s good reason to believe that Jones’ injuries are at least partly a function of how he’s been used.

Among top-performing backs, Jones gets an astonishingly low percentage of his touches via the passing game. Over the past two seasons, Jones has been used a lot more like a power back than the space-oriented player he truly is.

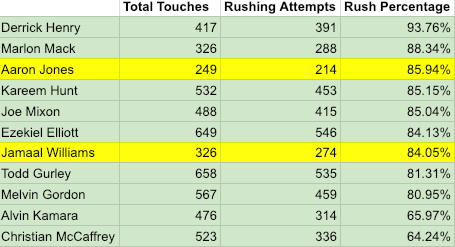

Using Football Outsiders’ DVOA metrics, I identified their top 10 best performing running backs and compared the Packers’ use of Jones and Jamaal Williams to how other teams used their elite backs.

As expected, Alvin Kamara and Christian McCaffrey ran the ball on only about 65% of their touches. More than a third of the time they touch the ball, it’s coming in space, where they have a chance to match up against corners and safeties as opposed to defensive linemen and linebackers.

But Jones runs the ball on more than 85% of his touches, the third most among the top backs in the league. At 5-9 and 207 pounds, his usage is closer to that of Tennesse’s hulking Derrick Henry (6-3, 247) than the more physically comparable Kamara and McCaffrey. If LaFleur can get Jones (and to a lesser extent, Williams) involved more through the air, it could lessen the physical toll he endures.

Even if Jones doesn’t end up with 35% of his touches coming through the air like Kamara or McCaffrey, LaFleur could still lighten his load considerably by changing how Jones gets his touches. Assuming Jones gets 250 touches next year (a slight increase over his 2018 usage), getting 25% of his touches through the air would result in a whopping 62 catches. That would be a huge increase for a Packers back, but it’s not that far out of line for teams LaFleur has coached recently. More importantly, it’s much more in line with how modern NFL offenses are using their backs, a change desperately needed in Green Bay.